Dubious Data: Debunking Dunning, Divorce, and Dexperts

I couldn’t find a good synonym for "expert" that started with "D"

Dissecting The Dunning Kruger Effect

In my opinion, the Dunning Kruger effect is one of the biggest belly flops in the social sciences — second only to the abomination that is “power posing.”

This is how most people articulate the dunning Kruger effect:

People with no skill at a given task will think they are extremely good at it, and thus be overconfident in their proficiency.

As they get better at the task, their confidence drops, because they realize how much they actually don’t know.

As they continue to get better, their confidence slowly rises.

This trend is summarized in the graph below:

Although, this is not the Dunning Kruger effect — like, at all.

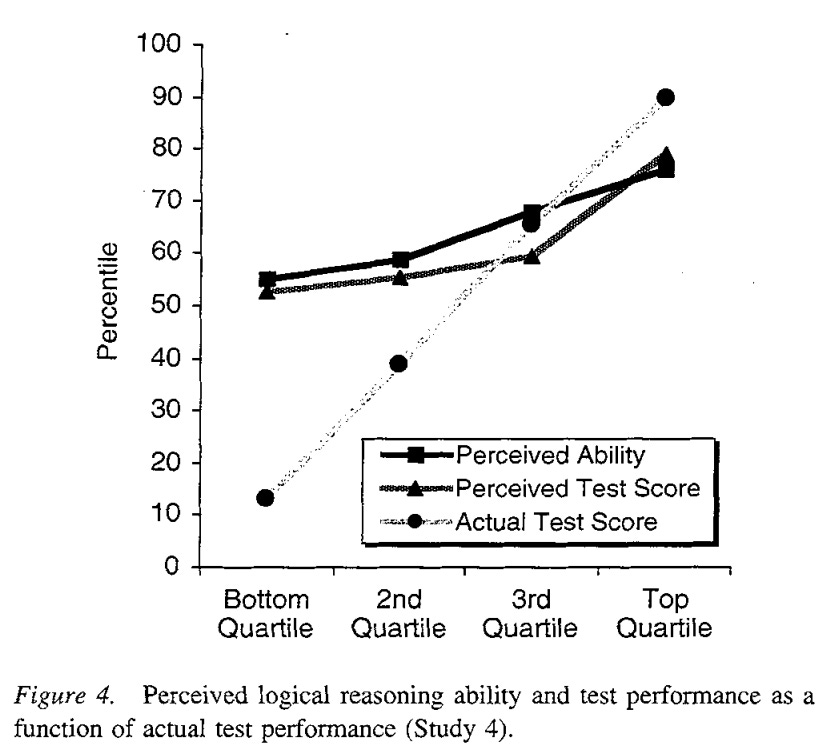

Here is a graph from the actual study:

Yes, it is true that the people who performed the worst on the task severely overestimated their abilities — but the slope of the line is still in the correct direction.

That is to say, the people who actually did the worst reported so, and the self perceived score rose with their actual score. And more importantly, it has nothing to do with emotions and confidence.

But my problem with the Dunning Kruger effect goes deeper than this. Personally, I find the whole methodology to be rather dubious.

There are already a few people who have pointed holes in the data using fancy models but I want to poke my own holes from a completely different angle.

When we look at the graph from the study, noticed that the data is already aggregated into quartiles. While this gives us a cleaner looking picture, it takes away the variation, and therefore deprives us of key information.

For example, for the people in the lowest quartile (who severely overestimated their score) was this the case for every single data point? Or did most people report the score accurately, with only a couple of data points severely overestimating the score?

Based on the graph as it is presented, we simply don’t know.

Further, and most importantly, there is an aspect of the Dunning Kruger effect which I find patently obvious — which, as far as I can tell, nobody is talking about: The ability to self assess one’s ability at something depends on the domain and context.

In the original study, the participants were tested on three categories: Logic, Grammar, and — if you can believe it — Humor.

Let me repeat that: they were tested for their humor.

Ironically, it makes me laugh to think about a group of study participants quietly sitting at their desks, filling out a Scantron card to figure out which one of them is going to be the next Kevin Hart.

But back to the point: it occurs to me that these subjects are inherently… well, subjective. Moreover, there are clearly domains where it’s a lot harder to misperceive one’s ability.

For example, I have literally never played a full regulation game of American football in my life. I legitimately don’t know how many players are on the field at any given time — but that doesn’t mean I’m going to walk into the NFL combine thinking I’m going to crush the competition. Similarly, from a lifetime of being a student, it’s clear to me that the people who are terrible at math are incredibly aware of it.

All of this is to say that, if we really want to take the dunning Kruger effect seriously, we need to start replicating it across a number of domains.

Dissecting No Fault Divorce

It’s been pointed out that no-fault divorce in the 1970’s allowed a lot of couples to, well, get divorced.

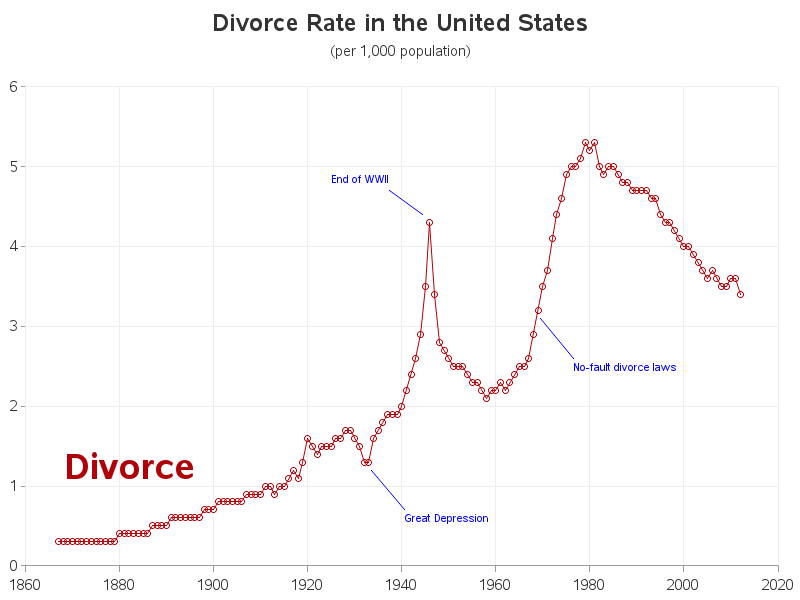

But the thing is, that’s actually not true. Here’s a graph of marriage and divorce rates:

The most eye catching thing is the spike right after World War II, which comes from the fact that, when the war ended, there was a pretty large reshuffling of demographics.

Basically, women realized they could work jobs, and didn’t want to be relegated to the home anymore; simultaneously, men realized they would actually have to live with their wives for the rest of their lives. Remember, most of these young men were 18 and got married to their sweethearts after only a couple of weeks. At the time it made sense because they didn’t know if they would be coming back from the battlefield.

But then there’s the second spike — the one about no-fault divorce. If we look closely at the trendline, we noticed something peculiar: it was going up before the law was enacted.

Thus, we have a classic case of mistaking correlation with causation — that is to say, we got the cause and effect backwards.

People wanted to get divorced, so they were coming up with all these obscure reasons why the marriage would no longer work out; the government eventually caught on, and was swayed by the social pressure to make this process easier.

And if you think about it, this makes more sense — when is the government ever ahead of social change? Alcohol, cannabis, gay marriage, racial integration… These were widely accepted in the culture before the laws were ever amended.

Dexperts — er, Experts

I’ll keep this one short and sweet.

Daniel Gilbert is one of my favourite psychologists; he has a Ted talk that’s really great — the opposite of power posing, if you will.

Recently he published a study along with a couple of colleagues dispelling a widely held belief: that experts are any good at giving advice.

As far as I can tell, there’s a few basic reasons why this is true:

The curse of knowledge. Once you know something, it’s very hard to go back to a world where you don’t know it. For example, if you are trying to learn a foreign language, it might be better to learn it from someone who learned it when they were in their 30s, rather than someone who is born into that language.

Unstated priors. Put simply, people mistake what works with what works for them.

Skill sets. This one is the most intuitive to understand, but one that people frequently glossed over. There’s a simple fact that being good at some thing and being good at teaching sometime or two entirely separate skills. Any first year stem student has learned this fact the hard way.