Question.

What do The Last Psychiatrist, Khabib Nurmagomedov, and the Breaking Bad showrunners have in common?

We’ll get to this, but first we have to talk about...

The literal greatest tragedy of 2024 so far

I’m largely positive on Cal Newport's work. With the release of his latest book "Slow Productivity," I went back summarized his underlying message in my previous post, as well as providing a number of critiques and implementations of his methods.

When it comes to the productivity space, his advice tends to be more grounded and practical than the majority of online content creators — which is admittedly a fairly low bar to overcome, given the majority of creators in this particular corner of the Internet are spouting crypto nonsense or doing… whatever the hell is going on here.

And so it was nothing short of a tragedy to see him post this the other day:

People who follow Cal Newport can easily acknowledge the contradiction of this video. This is a man who has spent over a decade talking about reclaiming your attention, developing a craftsman mindset, improving knowledge work, and avoiding all the pitfalls of social media — and here he is posting the same sort of clickbait “Rat Race” nonsense as everybody else.

Perhaps he could be forgiven if the interview itself lived up to the thumbnail and title, but after listening to the first 30 minutes, I can readily conclude that it’s the same Gary Vee style pablum you might hear at any sales funnel course that offers to change your life in a simple eight week program.

But the point of this post isn’t to rail on Cal Newport; rather, coming across that video solidified something about the online information landscape for me. Specifically…

Yep, incentive structures still matter

This is a subject I've written about rather extensively, from my very first post on this platform. From “engagement at all costs” nature of social media, to the “publish or perish” nature of academics, to, like, all of politics; the opioid crisis, financial crisis, housing crisis, and just about every other crisis you can think of can be boiled down to terrible incentives.

To summarize the online epistemic landscape, allow me to quote the Back Street Boys:

I don’t care who you are

Where you’re from

Don’t care what you did

As long as you love the algorithm

One particular aspect of the online information landscape which has become increasingly clear to me is this: even relatively high quality content pollutes the overall body of knowledge.

Some examples:

Mark Manson, the author of The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck — or as I like to call it, Buddhism 4 da Boyz — recently launched own podcast under the same name. His whole value proposition was packaging self-help content in a new and edgy way — and yet his interviews are exactly the same as, like, 20 other podcasts.

Jocko Willink, Navy Seal and literal Gears of War character, went from distilling the principles of leadership throughout his time spent at war to interviewing Dwight Schrute about his high school drama class.

Jason Pargin, the author of the only two online self-help articles worth reading (1,2) is now posting the same low quality Tik Tok videos for the sake of “engagement.”

(Edit from the future: Fair play to Jason — while I was writing this he himself acknowledged the very same point in his most recent post).

Andrew Huberman — who’s probably done more for popularizing neuroscience to a general audience than any other academic aside from David Eagleman — is now diving into the same biohacker human optimization content as everybody else. At this point you have to be a literal millionaire in order to afford his supplement protocol.

(Another edit from the future: I have been working on this post for some time, but I guess it would look strange if I did not address the recent Andrew Huberman shenanigans. I guess now we know how he was using his five free travel packs of AG1.)

"You're a fool if you look up to any of these people, or take any of their advice seriously," you might be thinking.

The operant word here is relatively high quality content. Whether you want to acknowledge it or not, the examples listed above fall on the right side of the bell curve. Again, for the Internet it's not exactly a high bar to clear.

So let's breakdown how the epistemic landscape, er, breaks down.

The pollution happens in three separate yet related ways.

First, the "anime" problem.

One of the reasons why content creators post on a regular schedule is to satisfy their advertisers. This means that they have the same problem as most old school anime; occasionally they have to create "filler" episodes — a plot line or character arc which is not present in the corresponding source material.

In the productivity self help world, filler episodes allow the podcaster/video creator/author to stray away from their main domain of expertise and delve into more experimental/tangential subjects. Usually this means opining on the culture war, as any opinions on such subjects are abstract enough so as to be unfalsifiable.

In principle there's nothing wrong with filler episodes, as long as creators make it clear the degree to which they have confidence in their assertions. For example, the physicist and philosopher Sean Carroll frequently has episodes outside of his domain of expertise, where he provides his opinions on artificial intelligence, the singularity, and the social ramifications of a changing technological landscape. Nevertheless, he is careful to preface his opinions with the degree to which he feels confident in the correctness of his assertions.

Most content creators who end up with an anime problem opine as authoritatively on these tangential subjects as they would their main focus of expertise, leading them down the grifter/guru pipeline, or as I like to call it "Epistemic Enshittification."

Second, the “LinkedIn” problem.

This is most easily explained by providing several examples from the podcast "Diary of a CEO."

In the last two months the host of this podcast has had no less than one, two, three, four, five, six different health experts on to give guide advice, each of which contradict one another. Even in the comments of these videos, the people are confused as to what advice they should actually take.

In a rare moment of simultaneous self-awareness and lack of self-awareness, podcaster Chris Williamson acknowledges this issue while completely sidestepping any responsibility for it about 1 hour and 13 minutes into this video. He basically puts the onus back onto the audience to decipher which pieces of advice are actually applicable to their situation.

This effectively makes the information useless; without providing a framework as to when either piece of advice is applicable, and to who, then it doesn't matter. One might as well not take the advice in the first place.

Nowhere is this more apparent than on the Social Media app LinkedIn.

One half of the posts on there are something along the lines of “Mental health is important, it's OK to want work life balance” and the other half of the posts are “This is Cindy. She has no arms or legs. She’s going to Harvard next year. Cindy is 8 years old. What have you done this morning?”

Anybody who tries to implement the tools and information on these feeds would effectively turn into a schizophrenic.

(And yes, LinkedIn is a social media app just like all the others. While Instagram and TikTok promote outright bragging, LinkedIn promotes humble bragging, disguising the status signaling behaviors behind the language of gratitude.)

Another edit from the future: Turns out Scott Alexander himself has written about the same problem, explaining that people who expose themselves to a particular type of advice might be the exact wrong type of person for whom the advice is intended, and offers the following algorithm to make such a judgment:

1. Are there plausibly near-equal groups of people who need this advice versus the opposite advice?

2. Have you self-selected into the group of people receiving this advice by, for example, being a fan of the blog / magazine / TV channel / political party / self-help-movement offering it?

3. Then maybe the opposite advice, for you in particular, is at least as worthy of consideration.

So perhaps more ozempic hippies from the Upper East Side should watch David Goggins, and more navy seals should read bell hooks. But regardless of your background, I think we can all agree that a utopian society is one where LinkedIn is no longer a thing.

Third, the stack ranking problem.

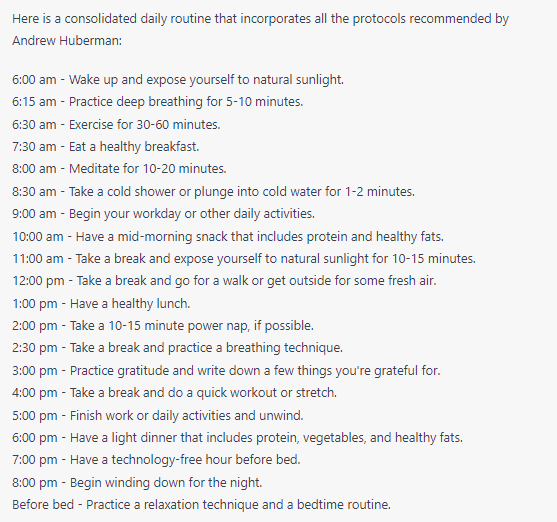

Again, this is easiest to explain by way of example; a reddit user once asked chat GPT to consolidate all of the practices and health protocols by Andrew Huberman into a single list.

See if you notice the issue:

This is fundamentally the problem with most content on the internet: by definition it's going to be vague and generic, and basically impossible for most average citizens to actually implement.

Multiple people could be experiencing the same problem — let's say, anxiety. Some of them might solve this problem through better sleep; for others, it might be an exercise issue; for others still, it's going to be something that requires pharmaceutical interventions. Meditation, omega-3 deficiency, relationships... any and all could be a contributing factor.

Again, the amount of information these creators provide is not the issue — and in the majority of cases the quality isn't an issue either. Rather, fundamental problem is the lack of indexability. A carefully curated library with a million books is going to be easier to navigate then a random pile of five thousand.

Sigh, another edit from the future: once again our Lord and Savior has already written about this, where he explains how he made his way to Haitian city office, and how the people working there didn't understand alphabetization as an abstract concept. As a result it would take the workers several hours to retrieve a single document from a shelf, considering they would have to go through the entire pile from scratch each time.

The modern information landscape is, for lack of a better term, an online version of the Haitian city office.

Conclusion... wait, are you going to answer that question from the beginning of the post?

What do The Last Psychiatrist, Khabib Nurmagomedov, and Breaking Bad have common?

Turns out AI image generators don’t let you create an image of an MMA fighter smoking meth while reading “Who Bullies The Bullies?”

They all had a moment in their respective careers where they said, “Yeah, it’s time to end this.” They said what they needed to say, did what they needed to do, and then shut down shop — even when it ran antagonistic to the incentive structures of their respective ecosystems.

The Last Psychiatrist could easily be posting clickbait to this very day, making snide remarks against a fashionable out-group who are actually part of the in-group. Khabib could have earned McGregor level money for his next couple of fights given the hype and dominance he displayed — coupled with his ability to galvanize the wealthy Middle Eastern fan base. The Breaking Bad showrunners could have ran the show to the ground until it was (walking) dead.

In fact, regarding The Last Psychiatrist, my pet theory as to why he stopped posting is that he realized that the majority of his content was doing nothing except creating miniature versions of himself — with all the snark and grandiosity without any of the wit. His audience was precisely the type of people who did not need his message.

Actual Conclusion

Regarding the online epistemic landscape, I'm growing increasingly convinced:

For consumers, the frictionlessness of the internet itself coupled with the rise of artificially generated content is going to lead increasing numbers of people to effectively declare bankruptcy on online epistemics, especially with respect to the self-help space.

For creators, the only way to truly avoid falling into the black hole of Internet incentives is to have a "Series Finale" of sorts, whether it's a blog, podcast series, YouTube channel, etc. — a moment where you've exhausted all the things that you need to say, and simply hang up the gloves. Of course, most content creators won't do this, because it is too lucrative to shout pablum.

Anyways, thanks for reading. As a reward for making it to the end, I offer you the following promotion that I've set up with my long and trusted sponsor Athletic Greens:

If you head to athletic greens [dot] com and type in promo code INCETIVE STRUCTURES, you'll get five free suppositories and an “Optimizing your infidelity” protocol at check out.