Introduction: Does money actually make us any happier?

Over a decade ago, Nobel Prize winning behavioural economist Daniel Kahneman published a paper saying that happiness tends to flatten out after (roughly) $75,000.

In response, Mathew Killingsworth published a separate study on the same subject, concluding that wellbeing continues to rise in a linear fashion in relation to log(income).

Recently both parties came together in order to understand why they came to different conclusions, publishing their insights here.

Contrary to popular opinion, I'm not a homeless wretch who screams at pigeons — I only do that on the weekends. In reality, I’m gainfully employed as a data analyst — and from this perspective it was interesting to see how they came together to analyze the results they got from their data.

Let’s break it down. Mo money mo problems or nah?

The initial passages of the collaboration bring cause for skepticism:

“We discovered in a joint reanalysis of the experience sampling data that the flattening pattern exists but is restricted to the least happy 20% of the population.”

In other words, they didn't really conduct any new studies. Rather, they reviewed original data again. This already creates the groundwork for the biggest criticism about this collaboration. The passage below makes it clearer.

“We later agreed that both studies produced valid results and that it was our responsibility to search for an interpretation that explains both findings.”

They’re assuming up front that both of the studies are completely correct. They are retroactively trying to find an explanation which reconciles both of the papers while disregarding neither. It’s unclear to me whether this is common process in academia, but it comes across as unscientific to deny that possibility that either (or both) of these studies is actually wrong.

Another passage of note, related to the distribution of the data:

“The authors of both studies failed to anticipate that increased income is associated with systematic changes in the shape of the happiness distribution.”

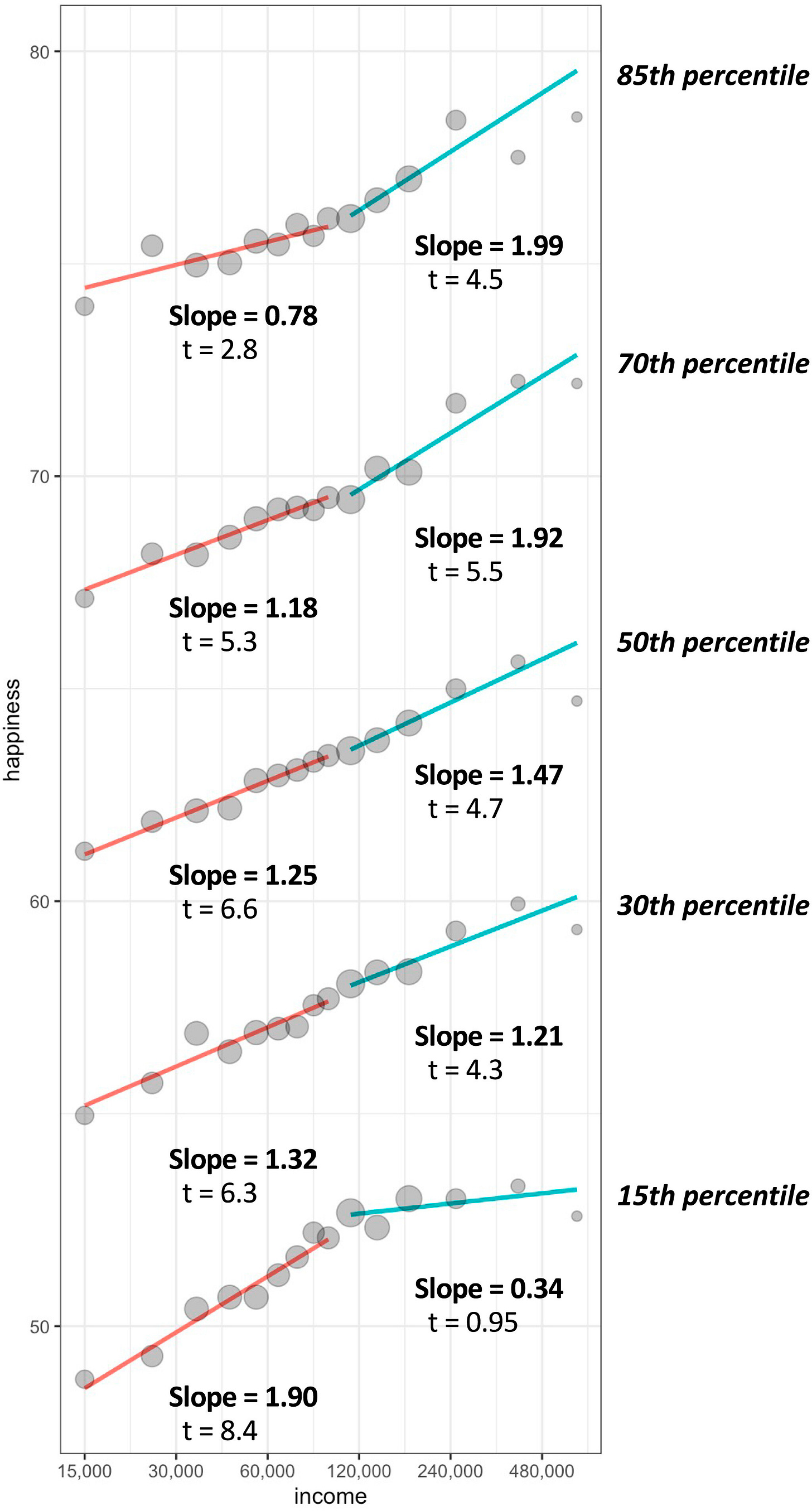

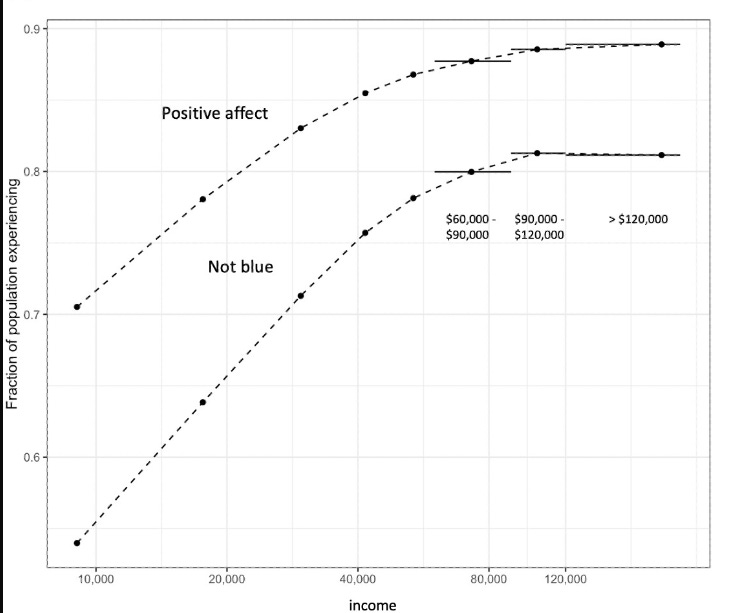

In other words, if they break out the Killingsworth data into smaller subsets (quintiles, in this case) the graphs will have a different shape than the overall aggregated result.

This is their graph; the top line looks more like an exponential curve while the bottom line flattens out logarithmically.

I find it puzzling why they would have any prior inference as to what the shape of the distribution would look like.

If anything, this is the reason why we need another study. It would be interesting to explicitly test this hypothesis. We might split study participants into different groups — those who define themselves as constitutionally unhappy, those who consider themselves relatively normal, and those who find themselves almost irrationally positive in their disposition. Then we would be able to see if there assumptions would hold.

An Aside: How exactly do you average out happiness?

One interesting yet overlooked variable was the sampling frequency. The Kahneman study sampled the participants happiness level once per day, while the Killingsworth study sampled three times per day.

This raises an interesting question about how we take the “average happiness” over a given timeframe.

Let’s say we have a graph of happiness on a given day which looks something like this:

What exactly is the overall happiness for that day? Do we take some sort of weighted average, treating all the time points as equal? Or are there some values which are considered more representative? Intuitively, I would rather have a day that starts off mediocre but ends up well rather than the reverse.

Then there’s the degree of variation. Being at a consistent 75% in terms of happiness would arguably be more preferable than constantly fluctuating between 25% and 95%, even if it averages out to 80%.

Moreover, there is the subject of Kahneman's previous work, Thinking Fast and Slow, where he distinguishes the experiencing self from the remembered self. What happens if I have a very bad day, but some time later I reflect on it and realize that it was extremely beneficial for me? How does one take that into account?

The biggest critique of the data

If we drill down to the lowest quintile of the happiness distribution, the Killingsworth data starts looking like the Kahneman data. Both data sets have a similar sort of flattening.

Killingsworth’s data:

Kahneman’s data:

This is how they come to their ultimate insight:

"We discovered in a joint reanalysis of the experience sampling data that the flattening pattern exists but is restricted to the least happy 20% of the population."

On some level, this seems intuitive. People in the bottom quintile most likely have problems that money can't actually solve: health problems, trauma, a disruptive childhood, etc.

But this raises the question of why Kahneman found this levelling off curve for the entirety of his data set. In order to compare apples and apples, one would have to break down Kahneman’s data into its respective quintiles as well.

The collaboration doesn't do this. Instead, they offer a reinterpretation of Kahneman's original study:

"We believe that if [Kahneman's study] had labeled their scale “unhappiness,” they could have concluded with confidence that the flattening pattern applies to a category of unhappy people. We also believe that they would have had no grounds to infer that the happiness of happier people flattens in the same way."

If I understand the argument correctly, Kahneman found a flattening pattern because they were actually measuring some sort of misery or suffering, rather than happiness. In which case, it makes sense to see the flattening curve, because going from poverty to middle or upper class allows us to remove the immediate stresses of being broke. But after that, there is really only so much misery that you can remove before you have to be more careful about how to invest in your happiness.

Fair enough, but the collaboration seemed to be playing a semantic game. Again, it needs to be backed up by some additional data collection. If Kahneman is going to be reevaluating what he believed the participants were answering, it makes sense to do another study where this is explicitly stated. If we’re talking about misery, then let’s actually talk about misery.

Now that most people have stopped reading, let's get to the fun part: The broader implications on academia and society.

On the one hand, it's laudable that Kahneman and Killingsworth actually took the time to bring their datasets together to find a common interpretation which reconciles their different conclusions. On the other hand, I believe this adversarial collaboration highlights a much bigger problem with social psychology.

The field has been going through some growing pains as of late, from the replication crisis, to the outright fraud by superstar psychologists Francesca Gino and Dan Ariely. In the latter case, both Gino and Ariely achieved prestige and recognition (as well as extremely lucrative careers) by publishing papers which were ultimately based on completely fabricated data.

I’m not accusing Kahneman of the same thing, but I think his $75,000 study highlights a parallel problem of the “academic literature to TED talk circuit” pipeline. Academics can become wealthy and achieve notoriety for studies which ultimately become defunct or otherwise lack nuance.

Because at the end of this reanalysis, the outcome is mundane and intuitive: “Money will make you happier, except if you’re a miserable person by nature — in which case money will only make you slightly happier.”

It’s worth repeating that the reanalysis didn’t include gathering any new data. The Killingsworth study simply forced Kahneman to look at his old data again and come to a different conclusion.

In a sense, they get to have it both ways. They get the fame and paycheck when they publish such studies, and when the studies are questioned they can attribute it to “Moving science forward.”

I’m of two minds about this.

On the one hand, I think it’s our fault; the general population loves to take these studies out of context, cut away all nuance, and make sweeping lifestyle changes in hopes of finally achieving that balance between materialism and inner peace. It’s a little foolish to think that we can finally solve the happiness problem based off of a single social psychology paper.

On the other hand, I think the incentive structures of academia exploit this need from the general population. That’s why Gino and Ariely fabricated their data, and it’s why the $75,000 study became so popular.

Because at the end of the day, the vast majority of us kind of want the $75,000 study to be true. Most people will never become multimillionaires, so there’s a sort of comfort in knowing that those who do end up becoming multimillionaires aren’t actually that much happier than us.

Conclusion: more data required

Ultimately the discourse on the relationship between money and happiness requires a great deal more data. Off the top of my head, I imagine the following would be relevant factors:

How does inflation/the current cost of living factor into any flattening pattern? It's important to remember that Kahneman’s original study came out in 2010.

How does the type of income impact happiness? For example, inherited wealth versus entrepreneurship versus typical corporate ladder?

Moreover, does the happiness level at a given income level depend on how long they have been at that income level? Intuition tells me that people who have been at higher income levels for a very long time tend to be less happy than people who climbed to that income level very recently.

To what degree is money simply a proxy for status? Would it be better to have a high status job that pays less, or a low status job that pays more?

Where are the true notable milestones for income? For example, there might not be any major difference between making $400,000 and $600,000. They are both flying first class. But there might be a noticeable jump between $600,000 and $800,000 simply because they are able to afford a private jet now.

Thanks for reading, here’s a picture of me on the weekends:

yo i read this one while i was on leave & my partner & i talked about it for like a solid hour afterwards. the $70k study thing is so interesting to me, love the deep dive.

Whenever anyone brings up this $75K study, which is now quite old, especially considering inflation as my grocery bill can attest, I also question the motivation behind the study. Is it to placate us into accepting billionaires run the world and we get our teeny piece of the pie so we should just be happy? Or is $75K when we finally feel like we're not always struggling to pay for our basic needs? Does making $75K suddenly make you a happier, more well-adjusted person? In my experience, I'd say no, it doesn't. Cracking the happiness code is likely a combination of many factors, including having basic needs met in a way that satisfies the individual, which $75K may or may not be the bar to reach for depending on familial circumstances, location, etc. The metrics could vastly vary for a single person living in a rural area to a family of six plus elders in assisted care living in an expensive city.

And what have you got against pigeons? It's not their fault they lost their postie jobs after the war! They're no longer in the $75K tax bracket. Give them a break. ;)