Intro

There are many crises in the world right now: the loneliness crisis, the housing crisis, the masculinity crisis, the existence of pop country music, the ecological crisis, and the many geopolitical tensions.

In addition, recent years have called attention to the fertility crisis i.e. the steep decline in the number of children all throughout the world. This includes places that were previously associated with high populations and large family sizes (Asia, parts of the Middle East, etc.)

Some examples of articles covering the issue:

Altogether, the commentary around has been scattered, vague, and rather abstract.

To be clear, the formulation of the problem is relatively well defined: fertility is measured in the median number of children per woman, and if it falls below 2.1 then we have fallen below “replacement rate” i.e. the number of children are required in order to keep the population steady.

The think pieces point out the potential economic, social, and technological implications of a society where there are more elders than children — though any solutions they provide are usually generic and hand-wavy, or otherwise built on a tower of assumptions.

The overall vibe of these think pieces tends to come across as “People are NOT HAVING CHILDREN. It is BAD and SOMEONE needs to DO SOMETHING about it.”

As such, I’m increasingly left scratching my head as to what these think pieces actually believe the correct solutions are. Which is to say, not necessarily the results required, but the tangible process by which these results are going to be achieved. It’s easy to speak about overall outcomes in the abstract, but as a baseline, any fertility crisis think piece should be able to clearly answer the following three questions.

What timescale are we referring to?

Imagine that you have a friend Brian who runs up to you in a panic, existential horror on his face. Concerned, you ask him what happened.

He answers: “Did you know that we’re inevitably headed for the heat death of the universe?! All of matter is going to reach its highest entropy state, and nothing will ever change ever again!”

You’ve heard of the heat death of the universe. You know that it won’t be able to sustain life, but you also know that it won’t be happening for a long time. Like, at least six years.

Nevertheless, you try to commiserate with Brian over this recent revelation, but over the course of the next several minutes he becomes increasingly impatient with you. He can tell that you don’t actually seem to care about the issue.

“Don’t you understand?! If we don’t do something about this, the entire universe will be uninhabitable for humans! Physics as we know it is going to collapse in on itself!”

You point out that, yes, the heat death of the universe is most likely going to be bad for the humans race — but in order to begin addressing those distant concerns, we have a number of more immediate societal issues that need to be resolved in the interim — like why there’s a country remix of the hit song Tipsy.

Brian starts getting frustrated with you. “How does any of that matter when the entire universe is going to freeze?!”

In this scenario, Brian is a stand in for the majority of the fertility crisis think pieces; they point out the negative repercussions that a low fertility rate might have in the next 40 to 50 years, without explicitly defining why the world of 2060 or 2070 is more important than the world of the 2020’s.

Or, stated another way, why not try to optimize for the world of 2200? Surely by this year we will have created a system where productivity and humans flourishing isn’t so sensitive to the fluctuations of the population growth rate?

“Yeah, but 2200 is too vague and abstract, and way too far away.”

Indeed, and for the majority of the population — those who are concerned with gas prices and making rent — the year 2070’s is just as vague and abstract, which brings us to the second question…

Why should the majority of people care about this crisis?

The concerns appear center around two broad categories: economic and cultural.

The economic concerns have two flavors.

First, a concern that an inverted population pyramid means that current government social policies will no longer be feasible.

Second, declining rates of innovation.

Both of these concerns simply miss the forest for the trees from the perspective of the average person.

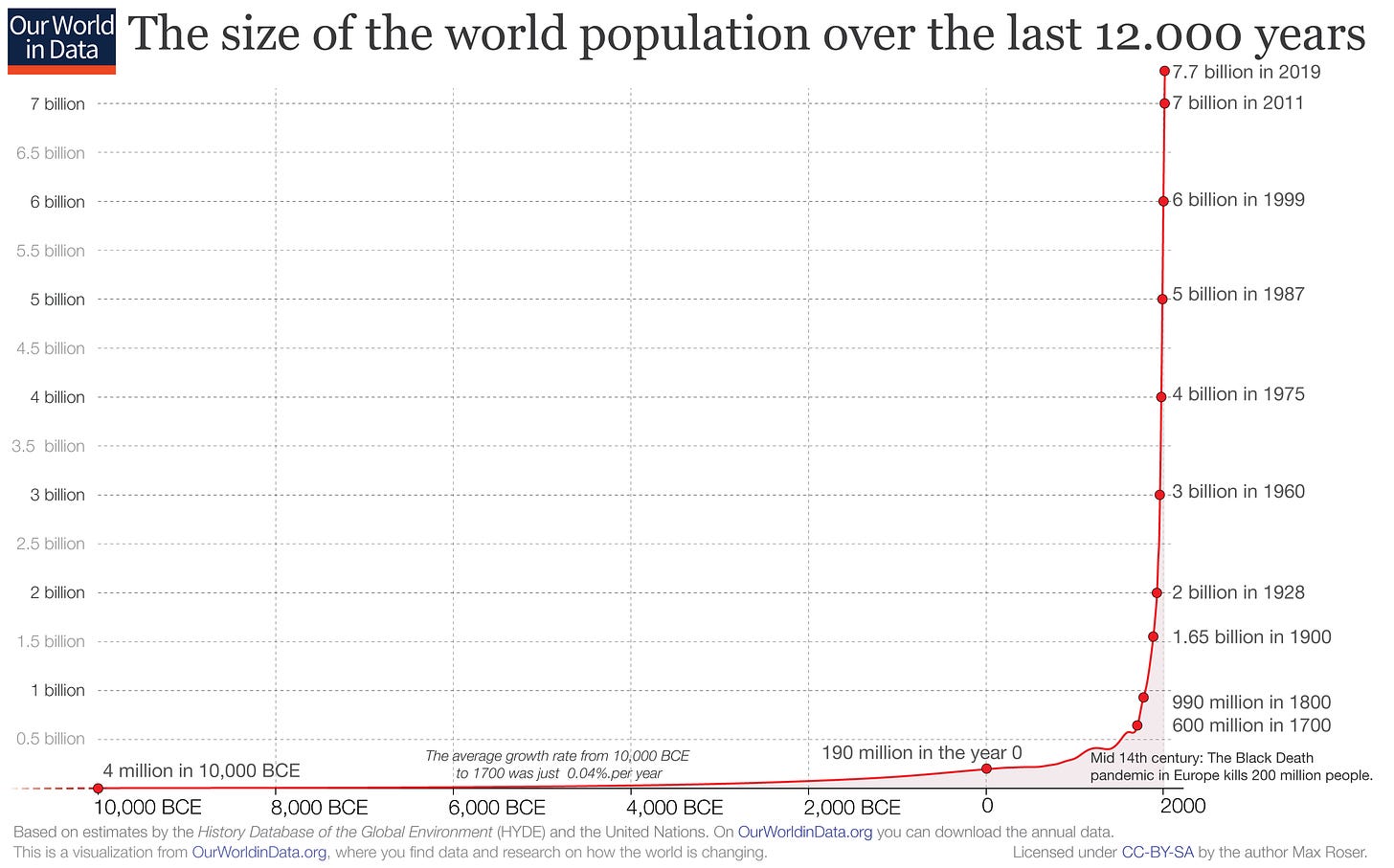

Taking the first concern, here is the human population over time, with an expectation that it’s going to continue growing until 2075.

If any slight decline in this growth rate means that a country’s pension/retirement/social assistance policies are going to collapse like a house of cards, then, honestly, it seems like you problem (you being the system, rather than the individual). One might even call it an intergenerational Ponzi scheme.

“No, but you don’t understand! You’re going to have to work longer, and even then retirement won’t be possible! Taxes are going to be unfairly high!”

If the punchline here is that the older generations have enacted policies and incentive structures which have systematically made life more difficult for the younger generations — I assure you that the younger generations have not failed to notice. Defined benefit pension plan? What is that? Landlords are colluding for greater profits? Color me shocked!

The second economic argument — pertaining to innovation — is contradictory. There are entire swaths of the tech sector who are building out systems where the entire point is to make human capital obsolete. Assuming they implement these systems, we might expect two possible futures:

The total pool of jobs that are necessary for a thriving economy goes down, in which case the economic concerns around a lower fertility rate no longer applies.

The total pool of jobs necessary for a thriving economy remains steady or otherwise goes up, which largely defeats the purpose of these technical innovations in the first place.

Regardless, both of these economic concerns simply miss the point of why people have children. I would venture that approximately 0% of people sit down and say: “Wait, French pension plans are going to be depleted by 2035? Let me ditch those Trojans!“

Which brings us to the second category: cultural concern. Going back to the Robin Hanson piece, sitting at the top of his tower of assumptions is that the future will inevitably be dominated by the Amish if we don’t jumpstart homegrown fertility. As a result, the majority of society will imbibe Amish values, thereby slowing down the current rate of innovation.

To state the obvious: if the Amish are going to be winners of the fertility crisis (in the west), then we need to acknowledge a fundamental truth about the way society is currently set up — prioritizing technological/economic advancement comes at the direct cost of community and family values, and vice versa.

Additionally, there is a sort of contradiction with the sort of people who have a concern about the population collapse from a cultural perspective: they tend to have libertarian/conservative views. And yet, I would argue it’s a borderline communist position to breed and reproduce for the sake of preserving the sanctity of “the state.”

Regardless, I’m less concerned with the actual “ism” drives the concerns around declining fertility rates; all that I ask is that the think pieces actually specify…

Who specifically should be having these kids?

Conservatives believe that “women” should start prioritizing motherhood again. OK, sure, but again I simply ask for specificity.

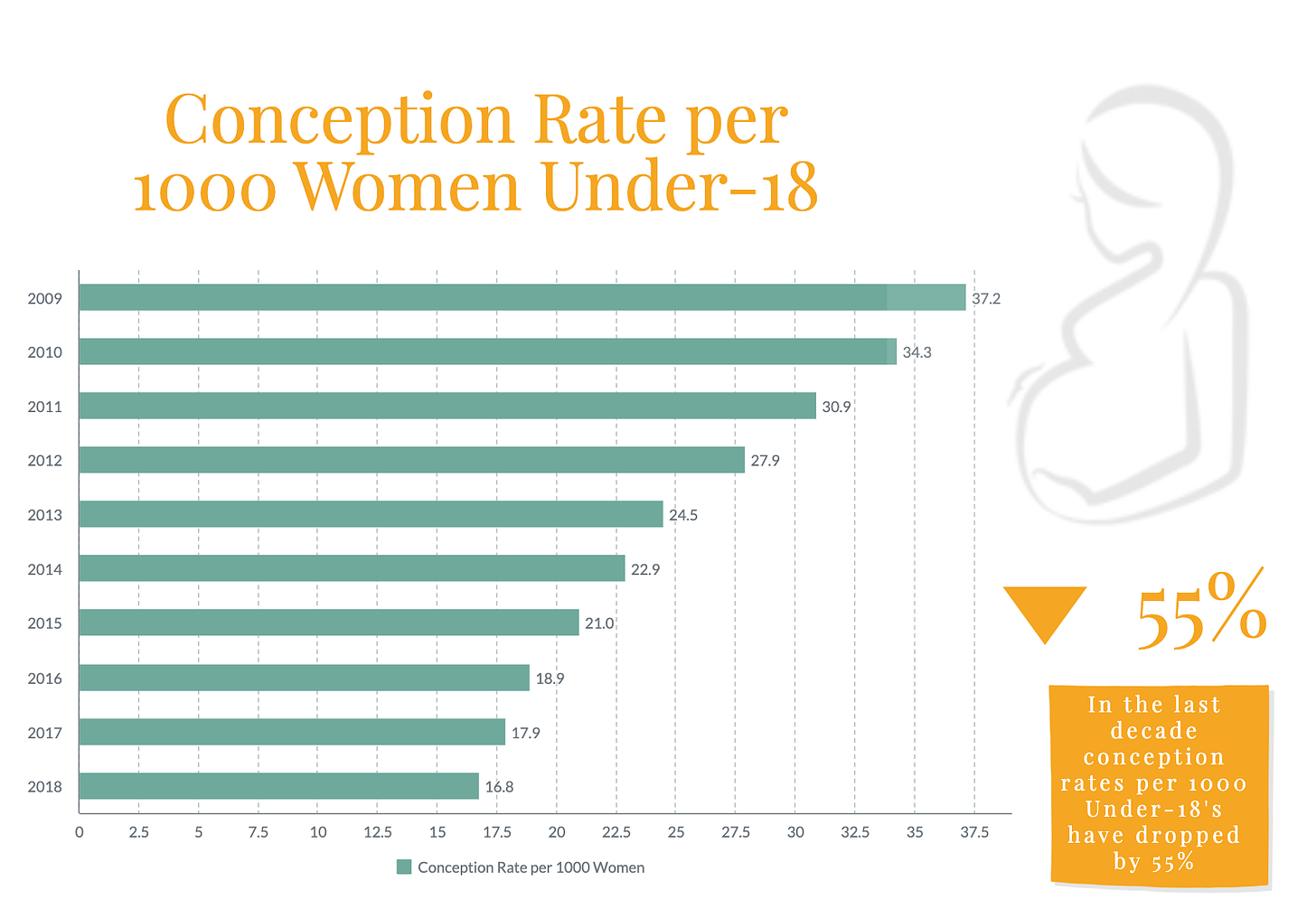

Here is a graph of teenage pregnancy over time.

Are you asking for this trend to reverse itself? Do you want more teenage pregnancies?

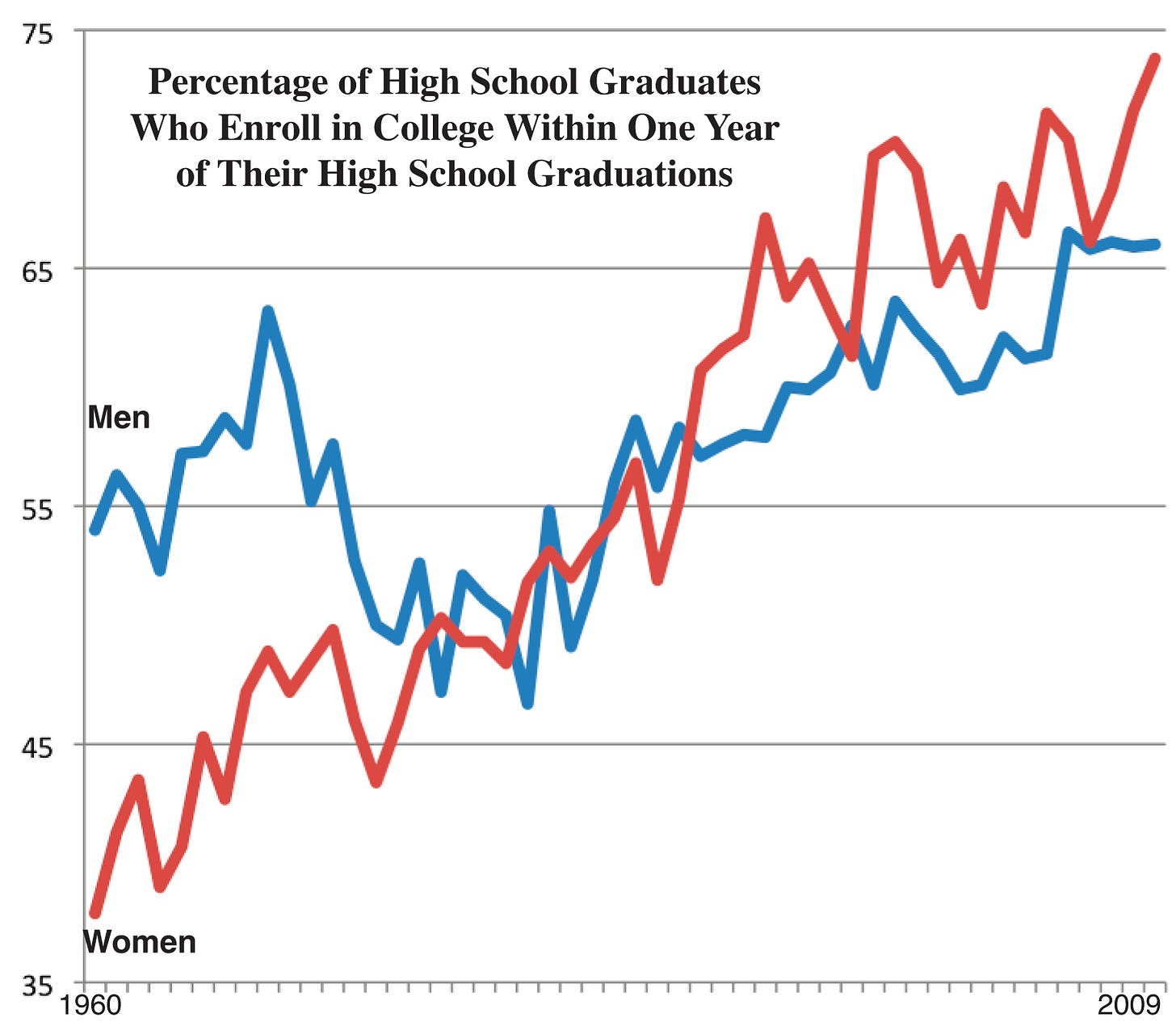

If not teenagers, then perhaps women in their early 20’s? In which case, are you asking that they drop out of colleges? Indeed, women make up the majority of college enrolments in the modern world.

Do you want the New-York-Times-reading DINKWODS to start having more kids? Who’s going to subsidize their maternity and paternity leave? Do you want them to go from middle to working class in order for this to happen?

Or maybe you have broader concerns with people who live in large metropolitan areas. You realize that people in big cities tend not to have kids, as the cramped environment tends not to be great for a developing mind. Are you asking that these people forgo the economic opportunities brought about by cities to start a much more rural and secluded life — where they are subjected to radio stations exclusive filled with pop country?

Or, perhaps you think the people who go on about ecological disaster, wealth inequality, or existential risk brought about by AI are simply foolish doomers. Are you asking that they just, like, get over it?

Do you want gay people to start having kids? At present only one in five same-sex marriages take up a parenting role to children.

Or, perhaps, your concerns stem from an evolutionary biology perspective. You’re worried that successive generations are becoming increasingly dysgenic. In which case, is your primary concern that you want the higher IQ people to start reproducing higher rates? Maybe you want to create some sort of PHD sperm bank?

Culture war aside, it would be great if people simply clarified their specific claims, because right now the formulation of any potential solutions rhymes with how the majority of middle managers at large bureaucracies address any technical problems:

Complain loudly about the existence of the problem

Set unrealistic expectations of how it's going to be fixed

Refuse to elaborate any further with respect to the technical aspects, or otherwise refuse to address any of the underlying concerns which brought about this issue in the first place

Nobody reads this far into posts, so…

… This is the part where I speculate.

In truth, my personal biases lead me to be rather ambivalent about population collapse. At the end of the day, people respond to incentives, both superficial and abstract. There are biological incentives, cultural incentives, economic incentives, and status incentives — and the majority of these incentives create a structure where having children is unilaterally infeasible for a wide swath of the population.

If the incentives are fixed, then the children will come. But the overarching message that lies one level underneath all of these think pieces is this: any concrete discussion about changing the incentives is unpalatable in the current moment, and therefore needs to be abstracted away.

This is because changing the cultural incentives is equivalent to chastising people who are childless; changing the biological incentives becomes a campaign of altering biological/reproduction rights; changing the monetary incentives suggest adopting social policies which privilege the young over the old — which usually won’t happen in countries where the old disproportionately vote, and the young disproportionately don’t. Changing the status incentives harkens back to the previous status hierarchies i.e. one provider, one homemaker.

With this in mind, the population crisis lays fertile ground (pardon the expression) for a much more uncomfortable discussion: Who in this world has the obligation to reproduce?

If this is beginning to sound like science fiction, or perhaps idle philosophizing, consider the trolley problem. For the previous thousand years, it was a little more than a thought experiment; with the invention of autonomous vehicles, we now need a practical answer to that question.

Similarly, technological advances are being made in the biotech sector. It’s my belief that, while AI currently dominates the headlines, the vast majority of the technological breakthrough will be more biological in nature. In some sense, this is already true; the most impact invention of the last decade may be the mRNA vaccine.

With increasing quantities of compute, massive data lakehouses which store all sorts of information, and more comprehensive AI systems that make sense of these data points, it’s only a matter of time until we have massive leaps in the field of genetics, medicine, and neuroscience.

With the current healthcare system crumbling, it will be eventually be replaced with more idiosyncratic treatments, tailored to the individual. Right now we use relatively crude measurements to distinguish one patient from another: blood type, family history, sex organs. It will only be amount of time until more fine tuned markers become the norm, such as DNA expression.

Of course, initially, these new therapies and molecules will explicitly be used for the purposes of rehabilitation. That is to say, to bring a typical person back to an acceptable baseline. But eventually these use cases will be set aside if the advantages prove great enough.

Things like Ozempic come to mind; already we see that majority of the prescriptions go to people who are not obese, but upper class men and women want to get even better shape than they already are.

And so the question becomes: what happens when we combine this twin phenomenon?

The biological revolutions that will take place over the upcoming decades, both in understanding as well as deployment of therapies.

A growing crust of society who is primarily concerned with plummeting population rates?

It’s not entirely ludicrous to think that these people make concerted efforts to force certain sections of the population have kids, while actively dissuading others. Of course, all of this will be done in an abstract manner, lest the E word get pulled into the conversation.

If you still think this is tinfoil hat nonsense, keep in mind that:

The companies behind the most popular large language models largely released their AI systems onto the open Internet before truly considering the negative ramifications. Even now, where there is a Nonzero probability of existential brisk, the concept of “move fast and break things” continues to drive Silicon Valley.

The fact that the guy who stated that “a collapsing birth rate is the biggest danger civilization faces, by far”, is also the guy who owns one of the largest social media platforms, as well as the company which wants to implant chips into your brain.

Thanks for reading

A few thoughts:

1. I also find that the innovation argument is kind of sidestepping the question. High population isn't required for innovation — the population of ancient Athens was maybe 100,00 free men and essentially spearheaded Western culture in a couple centuries. The undercurrent of the innovation discourse is that high achievers are declining in population, which is not often stated explicitly.

2. "Changing the cultural incentives is equivalent to chastising people who are childless" — I don't think this is necessarily true. For instance, medieval Christianity essentially valorized chastity and monastic life, but still had upward population growth because there were high enough birth rates among the non-celibate. The same applies for various Eastern religions with monastic traditions. This is definitely a tougher problem now since urbanity and education appear to inversely correlate with fertility, and top-down cultural change for pro-natal culture has proven to be very difficult. But I think this is the biggest conundrum that people are trying to solve: creating bottom-up pro-natal cultures that can still be appealing in the modern world.

This might just be a me thing, but the fertility crisis pieces I have read/heard in the past have had racist undertones. The reason they don't answer your third question is that there is no PC way to say 'more white kids pls'.

Although to be fair, it's not a topic I've done any balanced research on so I just get the views from some questionable corners of the internet I'm on.